The Adivasis in India, who have traditionally relied on forests for sustenance and livelihood, have been entrapped in a continuous battle with the Indian state which seeks to displace them from their forest lands in a bid to impose a model of development that favours corporate loot over the well being of the masses. Legislation such as the Forest Rights Act 2006 (FRA) and Forest Conservation Act 1980 (FCA) serve as political tools for the state to legally displace inhabitants of the forests for projects that are inevitably reliant on foreign capital and further the corporate loot of India’s natural resources. These laws also facilitate the imperialist model of development which exacerbates the pressure on the environment under the garb of “conservation” or in the name of farces like “compensatory afforestation.” The creation of exclusively protected areas like national parks, wildlife sanctuaries, and tiger reserves expands the exclusive influence of the state over larger tracts of forestlands. Whatever democratic space that the laws like FRA and FCA have been propounded to provide for the Adivasis is also being continuously eroded in the era of brahmanical Hindutva Fascism. After a 2022 amendment, which allowed the government to do away with the need for Gram Sabha consent as a prerequisite for approving projects on forestlands the Adivasis; the onslaught on the already diluted and dysfunctional legal safeguards for the Adivasis has continued with the new amendments proposed for the FCA.

The Forest (Conservation) Amendment Bill 2023, has been on the news, having sparked considerable controversy among the people and is currently awaiting discussion in the Rajya Sabha. This comes after its passage through the Lok Sabha in June with almost little to no deliberation. The changes that the new amendments introduce are broadly as follows: firstly, it moulds the term “forest” to remove relaxations granted by certain Supreme Court judgements with respect to what a protected area under the Act would be. Secondly, it grants an exemption for procedural requirements to be followed for clearing forests in border lands, in order to undertake “strategic linear projects of national importance”, allowing for a clearing out of forestlands and its populace to build roadways, railways, industrial projects in such regions. Moreover, an exemption is granted for areas affected by so-called “left-wing extremism”, ensuring that the government can stifle people’s resistance in the name of “national security”. Thirdly, the Bill permits certain non-forest activities, such as establishing zoos and ‘eco-tourism’ facilities (which are funded majorly by the World Bank, and serve imperial capital), on forest lands. This has detrimental impacts on the ecosystems of these regions, and on the populations that will be displaced and/or lose means of livelihood for the purposes of such projects.

What the Change in the Term ‘Forest’ Means

The central focus of the Bill revolves around a redefinition of the term ‘forest’ within the legal framework of India. It sets forth a provision wherein exclusively those lands designated as ‘forest’ in accordance with the Indian Forest Act of 1927, along with any pertinent legislation, or those officially documented as ‘forests’ within governmental records, shall garner recognition as ‘forests’ under the purview of the Act. To understand this further, it is essential to mention the 1996 judgement of the T.N. Godavarman vs. Union of India case, which centred on forest and wildlife conservation in India. It aimed to prevent illegal activities in forests, promote wildlife preservation, and enforce environmental laws, resulting in significant Supreme Court directives for safeguarding India’s forested areas. This judgement, by interpreting “forest” according to its dictionary definition, broadened the scope of the Forest Conservation Act. However, the result of this verdict on ground hasn’t been visible for the tribal communities. In fact, while the verdict might present the SC as a champion of environment and conservation efforts, the apex court has in fact been at the centre of legitimising and ordering the displacement of tribal inhabitants of forests , such as in a 2019 judgement where it upheld the rejection of 11.8 lakh claims of traditional forest dwellers on forest land, and ordered 16 states to hasten the eviction of the populations whose claims were rejected.

The revisions to the FCA will now also dilute the apparent and insincere legal safeguards that the Godavaraman verdict appears to have provided. According to the Forest (Conservation) Amendment Bill 2023, the Forest Conservation Act’s jurisdiction will be restricted to regions officially designated as forests in governmental documentation starting from 25 October 1980 onward. This will have the effect of leading to widespread forest land conversions for alternative purposes. The 2022 amendment had already eliminated the safeguards provided by the Act, such as the requirements for obtaining forest clearance permissions and seeking the informed consent of the local community. The regions poised for substantial impact encompass approximately 40% of the Aravalli range and 95% of the Niyamgiri hill range, which is inhabited by the Dongria Kondh, a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTG).

These changes not only give more power to the state when it comes to the conversion of forests for non-forest, corporate purposes, it also shows how the apparatus of law is being used to compulsively promote the development of an imperial, class based loot of our natural resources and land.

“The Burden of Development” : Development for Whom?

As is evident by a preliminary analysis of the Forest (Conservation) Amendment Bill, it propounds an anti-people model of development that rests on displacing the adivasis from the forest lands to support a model of development that is parasitic to these communities and detrimental to their lifestyle. The history of forest “conservation” laws in India is a history of a deliberate attack on tribal communities that have historically inhabited the Indian forests, in order to support the State’s vision of “development”. In the colonial times , the Indian forests were recognised as a landmine of resources for projects that would carry forward colonial “development”, help in building railways and offices that run the infrastructure of the colonial overlords. Hence, Dietrich Brandis’ model of development was introduced into the forestlands of India; in the name of “scientific forestry” forest lands were cut down and the plantation model that yielded timber for colonial development introduced. Over time, forest laws served to displace Adivasi communities so that the natural resources that had sustained the original inhabitants of these lands for centuries, could be exploited for colonial development projects. The Forest Rights Act, under the British government, classified certain forests as “reserved” and the tribal communities inhabiting such forests were displaced and disallowed from using any of the resources available in the forests- resources that had formed the basis of their livelihood. Rebellions by the people against this unjust takeover of their land were brutally suppressed by the British troops, as was seen in the suppression of the movement of the Bastar tribal population against declaring 2/3rds of their forest as “reserved”.

It is this historic model of displacing Adivasi people for a model of development that serves the interests of the State, and not the larger masses , that was carried forward by the Indian State after the transfer of power in 1947. The Constitution itself recognized certain areas inhabited by tribal communities as “Scheduled areas” which would enjoy certain rights to “self-governance”. However, this provision in itself gives the Governor of the State the right to decide whether or not a state/ central law applies in these areas- effectively placing the power in the hands of the Central Government. The assent of the Governor of the state is necessary for laws made by the “autonomous committee ” in this area- once again, placing the detrimental power in the hands of the Centre and exposing the myth of autonomy and democracy for tribal communities that these provisions tend to perpetuate. Legislative actions too, perpetuate a myth of a democratic voice for the tribal populations in matters of State action on land they inhabit. The Forest Rights Act post independence, particularly the amendment in 2006, were heralded as democratic laws that help Adivasi peasants assert their rights on the Adivasi land,by allowing them to get governmentally-recognized rights on forest lands- either through individual or community claims. However, the actual history of such claims suggests a reluctance on part of the Government to recognize community claims to forestland- with only 3.9% of total recognized claims (as per the FRA Status report,2018) being in favour of community land, while data actually suggests that 68.9% of forest land is inhabited and lived upon as community land. Moreover, there is a history of rejection of Adivasi claims on forestland in order to facilitate mining projects , as recently seen in the rejection of 72 claims from the Rinchi village in Jharkhand to facilitate a mining project in 2015. The reason given for the rejection is that the region contains a coal block, clearly illustrating that the government cares more about projects funded by, and providing resources to its imperialist masters, rather than for the well-being and survival of the Adivasi communities it rhetorically claims to protect.

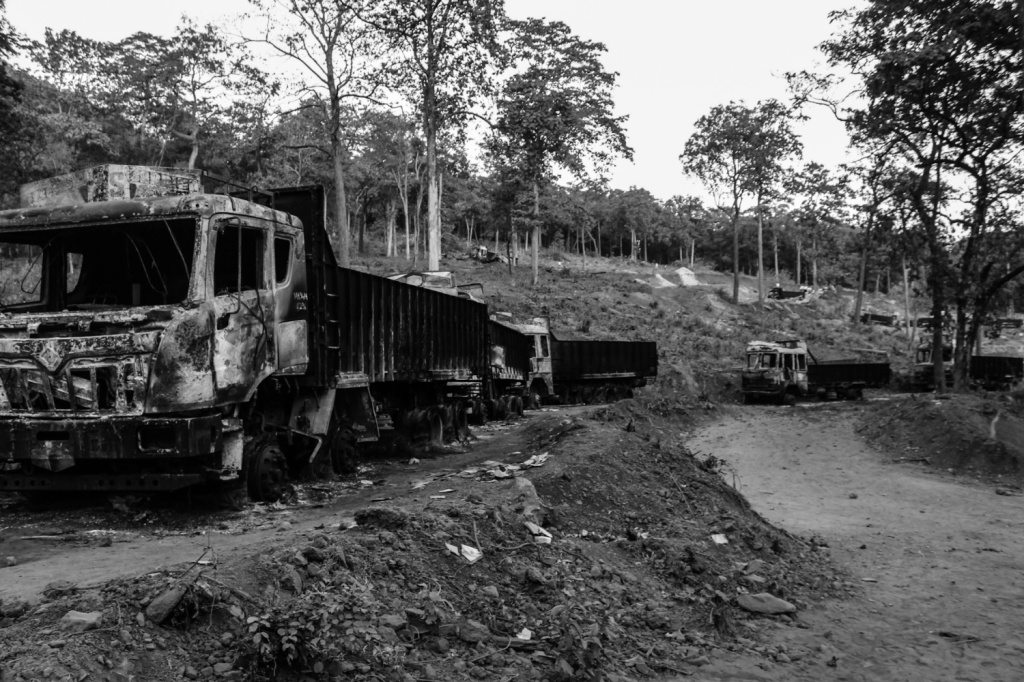

The alleged democratic structure of the 2006 FRA, has been reduced to nothingness by later legislations which severely diluted its essence. A look at the legislative history of Forest Conservation Rules, highlights that the 2022 amendment to the rules negated the need for Gram Sabha consent to developmental projects before they are passed, moving such “consent” to a stage when the developmental project has already been passed. The effect of the 2022 amendment and other laws in diluting the feeble democratic rights provided by the 2006 FRA is further explored in Political Economy of New Forest Conservation Rules in India. . Outright military repression has been used by the Indian State to support the interests of the comprador bourgeoisie (which is the section of the bourgeoisie that works in the service of imperial capital, and is supported by the State), such as the projects of Tatas , Birlas, Adanis, Ambanis funded by imperial capital are supported by military operations such as Operation Green Hunt (historically) , which has now been replaced by Operation SAMADHAN-Prahar. These military offensives of the State are an attack on the tribal populations inhabiting forest areas. Under Operation SAMADHAN-Prahar, the Indian State has gone so far as to aerially-bomb its own citizens in Chhattisgarh, in the name of countering Left- Wing Insurgency. This genocidal war being waged by the Indian State against the tribal populations is helped along by the new Amendments proposed to the Forest Conservation act. By exempting border lands for “strategic linear projects of national importance” , and importantly land that the government classifies as “Left-Wing Extremist Areas” in the amended Bill, the government will ensure that under the age-old shield of “national security”, it can clear out forest lands and populations and use the resources to further imperialist loot.

This outright war against the Adivasi population inhabiting India’s forests is justified by the State under the name of “development”. This development, they claim, will help the future of the country- help in urbanization, multinational mining projects, will help the “interests of the nation” as told by Nehru to persons displaced by the Hirakud Dam, marking the beginning of the “development by displacement” model as early as 1948. As per a study published in 2011, around 50 million people have been displaced in India due to ‘development’ projects in over 50 years. Of these, dams, mines, industrial development and others account for the displacement of over 21 million ‘development’ induced Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs). Of these, the Adivasis, constituting about 40%, are the worst affected. Industrialization has become the biggest cause of tribal displacement. In tribal regions 3.13 lakh people have been forcibly displaced due to mining projects and 13.3 lakhs tribal have been displaced directly from their ancestral land. This disconcerting state of affairs begs the important questions- what model of development are we following? Who benefits from this development and who suffers because of it? Why is this idea of development disproportionately burdensome on the Adivasis, villagers and natives of a region? The two former questions are answered by the nature of the companies, corporations and institutions that are behind these “developmental projects”. As explained in the prior sections- these projects are undertaken by the comprador bourgeoisie of India- that works in service of imperial capital, while several projects, such as those for building big dams like Sardar Sarovar, Tehri etc. receive funding directly from imperialist agents like the World Bank.

As discussed earlier, the proposed amendments to the Forest Conservation Rules will make it easier for the Indian government to legally displace tribal populations in the garb of projects of “national importance”, “national security” etc. Such displacement wreaks havoc on the lives of Adivasi people-depriving them of social sustenance, their livelihoods, their community land that they have held for centuries. Once displaced, the State is not entitled to provide them anything but monetary compensation. That too, as has been seen over several such development projects, the government has failed to provide what it was legally required to. Under these compensation laws, women are seen as extensions of their male relatives: they receive no separate compensation. Displacement for women in tribal communities exposes them to increased alcoholism and violence in marriages, they face early marriage and are often exposed to prostitution and human trafficking as a means of survival. Displaced populations are forced to migrate to cities, other industrial areas- in search of livelihoods. Here, they become cheap labour for other “developmental” projects of the state. Displaced populations are also exposed to poverty, chronic malnourishment, starvation and ill health, including serious psychological trauma.

Under the Garb of “Conservation”

In the garb of conservation, local communities are moved out of forests. This, it is argued by conservationists, is what is best for the environment. If Adivasi communities are not displaced when wildlife parks, sanctuaries are built; they are still deprived of their livelihood when they are cordoned away from their community land in the name of forest conservation. For example , for building the Sunabeda Tiger Reserve in Odisha, tribal hamlets were cordoned off from the forests that would constitute the reserve. They were forbidden from collecting Non-Timber Forest Products from the forests, which had been the basis of their everyday sustenance and livelihood. Moreover, the native Adivasi communities complained of harassment by forest officials and battled allegations that it was their lifestyle that had disturbed the forests. In fact, the building of biosphere reserves, zoos, sanctuaries, and eco-tourism facilities, all of which will be made easier by the new Rules, is more harmful for the natural ecosystem of the forests.

The pre-existing ecosystems in forest areas inhabited by the Adivasi communities include these communities living in harmony with , and as a part of, the natural ecosystem of these forests. Introducing eco-tourism facilities, building up “reserves” in the name of conservation has been proven to disturb the ecosystem for the people and the wildlife inhabiting these forests. In Mexico’s Pacific coast, eco-tourism has had the adverse effect of preventing female sea turtles from coming to the coast to lay their eggs (as they are now scared off by the crowds and lighting at the beaches), hence placing an already endangered species under further risk. The ecotourism initiatives themselves are only an attraction for the petty-bourgeoisie and “middle” or higher classes of society. For their entertainment in zoos, safaris, bio-parks/reserves, Adivasi communities face an unsettling displacement. These initiatives do not serve as a recreation route for the masses of the country, yet, they are displaced for them. Moreover, a lot of these “green investment” initiatives encouraging ecotourism are funded by the World Bank and WTO, specifically initiatives pushing private sector growth in the ecotourism area. Hence, the capital obtained from the eco-tourism initiatives will not even reach the Indian economy directly, it shall aid its imperialist masters. The justification of environmental conservation does not stand strong as a reason to displace adivasi people who are already living in harmony with the environment, only to put forth an imperialist model of sustainability that neither protects the environment nor reaches the masses of the country .

In this context, if we were to look at the current developmental model carried out by the Indian state, it becomes evident that it is in direct service to the imperial capital. It is not only a model that is centered around “land grab”, but it is also one which is parasitic to local populations and the interest of the working masses. This analysis of the Indian state’s nexus with its imperialist masters, and its devastating effects on the toiling masses , begs the question- what would a people-centric model of development look like and how would it differ from the current model?

A model that is centered around the needs of the people will come from the people, and will not be based in displacing populations from their traditional land. Instead, it would focus on the well-being of these populations, by ensuring equitable access to necessary resources. This would be a stark change from the current model where the mineral, power, and natural resources of India are siphoned off to foreign countries through the export surplus; and basic facilities like drinking water, food, healthcare systems are denied to the marginalized populations and toiling workers as they systematically only reach the well-off . The natural resources in the forests would be used to serve the populations inhabiting it, as per their needs, instead of being appropriated by the State. Workers who are subject to brutal exploitation under this developmental model , small and landless peasants, Adivasis who are displaced and left as cheap sources of labour or pushed into the reserve army of labour as unemployed; will be at the centre of this new model that will be truly democratic in that it protects the interests of the proletarian masses and not a small section of the bourgeoisie who are in nexus with imperial powers. Such a model would also be beneficial for the environment ,as it will be in the interests of the broader masses to prevent and mitigate environmental damage- as they are the ones most affected by such damage, be it through displacement by floods, environmental disasters, crop failure due to changing climate, or health problems caused by environmental pollution and degradation. This will be in stark contrast to the Indian State’s current model of valorization of foreign capital, which seeks for the expansion and invasion of capital into any space , regardless of its specificity. The failure of the current model is evident in the severe damage it has caused to the environment and people, be it in Joshimath where the environmental damage caused by the expansion of capital has led to deaths and displacement galore; or in the forestlands , where ecosystems are being destroyed and tribal populations are being legitimately displaced through the FCA, FRA ,or are even militarily attacked to enable developmental projects meant for the few, and not for the masses.

Conclusion

The Forest Conservation Amendment Bill is an anti-people legislation that furthers the Indian State’s undeclared war against its Adivasi population. The myth of bourgeois democracy is exposed by the manner in which the Bill was passed and the underlying motive behind it. As discussed in this article, the Bill will further help the State serve the interests of the Indian comprador bourgeoisie and their imperial masters, while the local communities pay the price for this model of development. This developmental model that this Bill serves out-rightly displaces, disenfranchises, and goes so far as to bomb local communities to clear the way for profit making developmental projects, is nothing but genocidal. Only an organized people’s struggle demanding the preservation of the peasantry’s land ownership and demanding land to the tiller can strike at the heart of the Indian state’s open terror against its own people. After all, when land is lost, the Adivasis will not be eating coal.

by Samyukta Kannan, student of law, Jindal Global Law School

References:

2. prsindia.org/billtrack/prs-products/prs-bill-summary-4096

3. The Forest (Conservation) Amendment Bill, 2023 (prsindia.org)

8. https://thewire.in/rights/supreme-court-eviction-tribals-displacement

9. https://www.prb.org/resources/eco-tourism-encouraging-conservation-or-adding-to-exploitation/

10. Roy, Arundhati. The Greater Common Good. Frontline (1999).

11. T.N. Godavarman vs. Union of India WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 202 OF 1995.

Leave a comment